| |

Poster

Design Guide

1. General

Information About Poster Sessions

2. Analyzing Your Audiences

3. Showcasing the NEWS about Your Topic

4. Visualizing the “NEWS” in the Design Space

5. Creating Coherence

6. Option: Using a Template

7. Applying Poster Style to the Text

8. Printing Your Poster

9. Preparing a Handout

10. Developing Expertise with Feedback

|

| |

A

Guide to Preparing a Poster

A poster must:

- meet

physical requirements determined by the session organizers,

- present

your IDEA about the topic and show why it is interesting

and important

Designing

a poster is a challenge because space is limited. It must

be lean and clean, standing alone if you are not present,

and gain attention as audiences come and go.

1. General

Information about Poster Sessions

Poster sessions are held as part of professional conferences, trade shows,

job fairs, and university courses or end-of-semester campus shows. Posters

of a predetermined size are displayed in a large area, and the audience

moves about as it chooses; presenters stand near their posters and explain

them briefly or answer questions. Poster sessions enable people to seek

information about new work with convenience and freedom in a short period

of time, a kind of cafeteria of information. Today's software programs

enable novices to prepare exciting, informative posters. Students as

well as professionals can participate in poster sessions. The "Resources" link

at the Cain Project web site can help you find specific answers to your

questions--such as, "How do I print my poster?"-- or help you

learn about the challenges in designing a poster.

The physical setting of a poster session sets the rules, especially the

size and materials you use in your poster. If large 8'x4' plywood

boards on frames will be used for poster display, you can make a

much larger poster than if the hall will have lightweight easels

that can hold 2'x3' cardboard posters. So pay attention to the rules

for your poster session: if the rules say tape can be used to secure

the poster to the frame, bring tape, not pushpins. However, sometimes

circumstances may shift after the time a session is announced; it

is good to bring a small kit along with other materials such as tacks,

Velcro tabs, push-pins, and masking tape or display clay to adapt

your poster to the situation.

A poster session's location makes travel or shipping part of the design

requirements. If a presenter must travel on a plane, a container

will be needed to protect the poster in transit. Poster tubes can

be purchased for around $2.00 to protect your poster duing transport.

Presenting at a poster sessions differs from giving other kinds of presentations.

The audience comes and goes, so the presenter must constantly adapt

to the viewers who are present. Some will want an oral explanation;

some will merely want to look for a few seconds. Prepare several

versions of your remarks, from 30 seconds to 4 minutes (Presenting

Your Poster).

Poster sessions are usually scheduled for particular hours, and presenters

may be asked to be present at specific times to be near the displays.

However, the display hall may be open at other times, too; it's a

good idea to make sure a poster can communicate well without the

presenter being there. It is crucial to know what materials are allowed,

what physical dimensions the poster can be, what display methods

will be available (tape, tacks, or Velcro), when the poster must

be put up and taken down, and how transporting the poster to the

conference or presentation site might affect success. Take along

tape, scissors, extra tacks or pushpins, and a packet of Velcro tabs

(available from a sewing, fabric, or crafts shop). Also check on

the physical constraints involved in using the computer: both printers

and software have size limits.

Back

to top

|

| |

2. Analyzing

Your Audiences

Characterizing

your audience during initial poster planning enables you to better

tailor its content and design elements to those you wish to reach.

The audience for the CHEM 215/217 session, for example, will

include your fellow students, your instructors, someone from

the Cain Project, and other invited guests. They have different

levels of knowledge and different interests.

- The instructors

and guests will be more expert than you are in organic chemistry.

Their questions will be more technical. They want to know

you thoroughly understand the mechanisms you describe.

- Your fellow

students will be interested, but their questions will probably

be more basic.

- The Cain

instructors may ask you design questions about your principal

point, your design choices, and your process.

These different

audience types will affect your content and design decisions:

- What critical

concepts/terms/issues will need to be defined for each audience?

?

- What visual

aids (tables, graphs, and so on) can be used to convey information

to audience members with a wide range of research interests

and experiences?

- What questions

can you anticipate audience members having about the information

conveyed in your poster?

- What questions

do YOU want to answer for these people?

- What organic

transformations are relevant to your purposes?

- What is

especially interesting or perhaps unexpected about these

transformations?

- What have

you studied in lab or in class that would help the viewers

gain a foundation for understanding the transformations you

wish to present?

- What colors

or designs are relevant to these compounds or processes?

- What applications

or products are related to these transformations?

- What experiences

or values would the audience connect to these products and

processes?

Thinking

about the questions above will help you showcase the "NEWS" in

your presentation.

Back

to top

|

| |

3. Showcasing

the "NEWS" in your Topic

The poster design process moves quickly when you take time to make some

early decisions:

- What's

the NEWS? What did you find out that you want to share with

others?

- How can

the overall arrangement of the poster signal the news?

- How can

all the elements reinforce the main idea?

- What will

make the reader stop and look?

To select the

content for your poster, you must cull the most essential information

from the wealth of knowledge you've gained. It's psychologically

hard, but you can't use EVERYTHING. You want to select the crucial

support for “The News.” You can rank the information

into three categories:

- MUST

know (to get the point)

(This includes the three-step transformation or the alternatives--one

two-step process plus a single-step process, OR three one-step processes,

hazards, etc.)

- Good

to know (equipment, size, volume, world production,

and so on)

- Nice

to know (perhaps historical or social context, cost,

unexpected effects)

You should

include the MUST, add some Good, and save “Nice” details

for talking with your audience or for a handout you'll give

them.

Back

to top

|

| |

4. Visualizing

the “NEWS” in the Design Space

The point of design is to make “The News” accessible and easy

to process by the audience, that strolling, fickle group of individuals

whose eyes are darting back and forth across the room. Help them get

the point of your poster with a commanding, large font title. Include

an introductory summary. Use message headings and forecasting statements

to introduce or sum up each section. Reduce jargon--people avoid things

they can't understand.

Choosing an overall layout appropriate to the main point of your topic

is the most important step.

Think of a quilt.

It's big and rectangular, and right away you notice a pattern. Similarly,

a poster should have a suggestive arrangement of communication areas.

Three of the basic news arrangements are horizontal areas, vertical areas,

centered images. Use your answers to the questions above to relate the

NEWS to a spatial layout that leads the audience's eyes through your

NEWS. Some of your choices are:

- left-to-right

flow in vertical columns

- two fields

in contrast

- left-to-right

flow in horizontal rows

- a centered

image with explanations

These are suggested

in the following thumbnail shapes.

This is the

most challenging part of design: matching the physical pattern

of the layout with the intellectual pattern of your NEWS.

- What are

you trying to show the audience?

- Is it

a problem and a solution?

- Is it

an image, for example, of a device or chemical reaction?

- Is it

a contrast? (old vs. new, before and after)

- Is it

a demonstration?

- A process

in series? (the three-step transformation may be shown horizontally

or vertically)

Group content

in appropriate areas. For example, if you have three main points,

you'll need three main areas plus the areas for the title,

summary and the acknowledgments.

Back

to top

|

| |

5.

Creating Coherence -

Constructing a coherent poster means that it’s easy for your audience

to move from one topic discussed on your poster to another and to see

the relationships between them. Create coherence by carefully planning

the arrangement of information by relying on what we know about how readers

read.

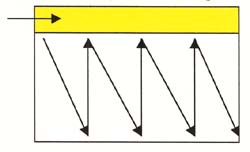

Since English-speaking readers read text from left to right and top to

bottom, use this pattern to inform the arrangement of information in

your poster. While the poster title is conventionally centered across

the top of the poster, it can be placed to the left or to the right,

but the area it occupies should command the rest of the space, perhaps

by using a colored area behind it, as shown below.

Pattern eyes follow in reading a four-column poster:

Other useful

strategies for guiding the reader's attention and showing the

relative importance of each part of your poster’s content

include attending to blank space, graphic hierarchies, indenting,

visuals, and color.

- Blank

space defines relationships among objects. Marginal

space around the sides and bottom creates an inclusive

frame for the content of your poster. Don't run text completely

to the edge of the poster. Leave some framing blank space.

Separate columns with blank space, too (although these

areas may be colored) so that the viewers' eyes can quickly

pick out the pattern or arrangement of content.

Use blank space to help dictate the scale of the information you present

and the visuals and text that communicate it. Are there three major

areas? Four? Five? The design should help the viewer know right away

where to begin.

Blank space tends to push a viewer's eye toward sections it surrounds,

but it seems to push apart text or images if there is too much space.

The meaning of "too much" depends on the overall size of

the area.

- Graphic

Hierarchies help viewers determine quickly which sections

are of equal importance and which are of lesser or subordinate

importance. Graphic hierarchies can consist of point sizes,

color areas, line widths, and so on.

The rule of thumb is: BIG = IMPORTANT small = subordinate

- Indenting information

helps to create white space around the information that emphasizes

it and makes the information easy to scan with the eyes.

You can indent information by generating bulleted or numbered

lists or by creating more white space around paragraphs or

other chunks of related visual or textual information.

- Visual

Aids. Arguably the most critical design elements of

any poster display include the use of visuals, font style/size,

and color. The effective use of these features helps to

make your poster both aesthetically pleasing and easy for

the viewers’ eyes to scan.

Posters are characterized by their use of both text and visuals. In posters,

visual aids such as tables, graphs, photographs (and a variety of other

discipline-specific visuals) can communicate a wealth of information. To

use these visuals to communicate information accurately and effectively,

it’s best to remember these tips:

VISUALS

TIPS

- Enlarge

visuals so that they’re easily viewed. Remember that

your audience typically views your poster from three to five

feet away. Use these distances when judging how legible all

aspects of your visuals will appear.

- Make sure

that any labels you use with the visuals are large enough

as well. Font sizes for these labels should be between 30-36

points.

- Number

and title each visual that you use and be sure to reference

them in the text.

- Think

of photos, drawings, and so on should be independent elements

that can be understood without reading a long explanation.

The heading and labels on your visual will help it stand

alone. Remember that your audience may only scan your poster,

and the visuals may be the only features they examine.

- Eliminate

any nonessential information (grid lines used in the background,

extraneous information used in keys) and try to redesign

your visuals to emphasis the most critical information you

wish to communicate.

- Remember

that photographs or other illustrations may be distorted

and difficult to read if enlarged. Double-check the clarity

of these visuals by printing them out before you print out

your entire poster.

Font

Style/Size. Improve legibility with the correct font

size. To make the information you display legible for your

audience, you must judge how close a reader must be to read

the smallest crucial piece of data.

Here is a guide to font style and size if your viewers are likely to

be three to five feet from your poster:

Serif fonts have "tails" (serif means tail in French) at the

base and tips of letters and have line widths that thin out on curves.

They are harder to read from a distance, especially if the contrast between

the letter and the background is poor. Sans Serif fonts have consistent

or uniform line widths or line widths that vary only a little. They have "no

tails" (sans serif means "without a tail" in French).

| Title

(6 – 8 words) |

(Arial

bold) (Arial

bold)

| 90

- 120 pt or more |

| Headings

(3 words) |

(Arial) (Arial) |

36

- 48 pt |

| Text |

Serif (Times

) |

30

- 36 pt. |

VERY

IMPORTANT: Headings of the same level of importance should be

in the same size and type of font.

All labels should be legible from at least 3 feet away.

Color. Color can “make or break” a poster’s

legibility and aesthetic appeal. Incorporating color appropriately

in a poster display means choosing and using color purposefully.

Use color to show:

- which

elements go together (are similar in value or are related

in topic)

- which

elements differ

For example,

if you use a background color for two different areas of the poster,

those areas should be related in some way. Back in the days when

people displayed posters by using by gluing printed pages to construction

paper, people sometimes used whatever colors came in the paper

assortment. While variety is pleasing, poster viewers want MEANINGFUL

variety.

In deciding how to use color in your poster display, here are some good

rules of thumb:

- DO use

color to show relationships among different areas of the

poster. Do use color to create coherence and guide your audience

through the sections of the poster. Do use color sparingly

and purposefully—less is more

- DON’T

use color arbitrarily; think about the ways color can be

used to show relationships and incorporate this strategy

into your poster. There must be sufficient contrast between

the background and the text or between the background and

the diagrams for viewers' eyes to read easily. Use light

colors for your text (such as yellow) ONLY if the background

is dark; use fonts with a consistent shaft width so that

the letters won't seem to "thin out" or disappear

when viewed from a distance. There must be sufficient contrast

between the lettering and the background.

Back

to top

|

| |

6.

Option: Using a Template

The Cain Project web site has poster templates (PowerPoint files) in

vertical and horizontal layouts at its website at that you can download

to your computer. Click on "Download Poster

Design Templates" from the Resources section of the Cain Project

web Site. These posters have Rice logos on them that you can keep or

replace. These can be used to jump-start your design process.

Back to top

|

| |

7.

Applying Poster Style to the Text of Your Poster

Put your text on a diet. Shrink fat text to lean text, as in this example:

| Original |

Revised |

| The

ideal anesthetic should quickly make the patient unconscious

but allow a quick return to consciousness, have few side

effects, and be safe to handle. |

Ideal

anesthetics

- Quick

sedation

- Quick

recovery

- Few

side effects

- Safe

to handle

|

Details

Matter!

Check for consistent formatting, correct grammar, and correct spelling.

Avoid abbreviations and acronyms a viewer may not know. Give a correct

bibliography. Give credit to others (to establish your character and

ethics), and include contact information.

Back

to top

|

|