Our household consists of my wife and myself. My wife is a vegetarian.

She only cooks and eats vegetarian food. I am carnivorous. I cook

and eat meat!

If my wife wants to eat broccoli and cheese, she can learn how to cook

broccoli and cheese.

If she wants corn of the cob, she can learn how to cook corn on the cob.

The same goes for me.

If I want to eat greasy hamburger, I can learn how to cook greasy hamburger.

If I want to eat fatty hotdog, I can learn how to cook fatty hotdog.

Every time we want to eat something new, we can learn how to cook it. This

requires that my wife and I to each have a very big head in order to learn all

the recipes. But wait, there are things out there called restaurants!

These are very special kinds of restaurants catering only to vegetarians and

carnivores like people in our household. These restaurants only have two

dishes on their menus: one vegetarian dish and one meat dish. All my wife

and myself have to do is to know how to call such a restaurant to order our

favorite dish.

My wife will only order the vegetarian dish, while I will only order the meat

dish!

How do we model this set up?

In the design pattern language, our household is called the host, and the

restaurants are called visitors.

To paraphrase Shakespeare, it's a matter of to cook or not to cook!

|

public abstract class

AEater { |

|

| public class Vegetarian extends

A Eater{ public Vegetarian(String address) { super(address); } public String order(IRestaurant r, Object n) { return r.cookVeggie(this, n); } } |

public class Carnivore

extends AEater{ public Carnivore(String address) { super(address); } public String order(IRestaurant r, Object n) { return r.cookMeat(this, n); } } |

When a class is declared as abstract, it cannot be instantiated, and in order for it to be of any use, one must define concrete subclasses for it Its purpose is to define zero or more attributes (aka fieds) for certain type of objects, zero or more default behaviors (i.e. methods with some code) for these objects, zero or more abstract behaviors (i.e. methods with no code body, declared as abstract) for these objects. If an abstract class has fields, usually they are protected, meaning they can be accessed by subclasses of the abstract class. Moreover, the existence of fields usually required a constructor to properly initialize these fields at construction time. Such constructors are usually declared as protected to make them only accessible by the subclasses. A constructor of a subclass must call the appropriate constructor of the abstract super class via the key word super, passing to it the appropriate parameters. A concrete subclass of an abstract super class must override all abstract behaviors of the super class. Any class with an abstract behavior must be declared as abstract. The syntax for making class B a subclass of class A is: class B extends A {...}.

An interface is like an abstract class with the special constraint that all methods must be pure abstract and have no code bodies. By definition, an interface and its methods are always public and abstract. Thus one need not declare them using the public and abstract attributes. An interface is used to specify a type without any concrete implementation. When a class implements an interface, it must provide concrete code for each of the methods in this interface. In Java, a class can extends only one other class, but can implement as many interfaces as it sees fit. This provides a form of multiple-inheritance that has proven to be quite flexible and useful in many advanced OO designs.

| interface

IRestaurant { String cookVeggie(Vegetarian h, Integer n); String cookMeat(Carnivore h, Integer n); } |

|

| public class ChezAlan implements

IRestaurant { public String cookVeggie(Vegetarian h, Integer n) { return n + " Brocoli and Cheese " + "delivered to " + h.getAddress(); } String cookMeat(Vegetarian h, Integer n) { return n + " Greasy Hamburger " + "delivered to " + h.getAddress(); } } |

public class ChezZung implements

IRestaurant { public String cookVeggie(Vegetarian h, Integer n) { return n + " Corn of the Cob " + "delivered to " + h.getAddress(); } String cookMeat(Vegetarian h, Integer n) { return n + " Fatty Hotdog " + "delivered to " + h.getAddress(); } } |

Suppose I am faced with the problem of computing the areas of geometrical shapes such as rectangles and circles. I need to build objects that are capable of computing these areas. The variants for this problems are the infinitely many shapes: rectangles, circles, etc. What I do is define concrete classes such as Rectangle and Circle, and make them subclasses of an interface, called IShape, which has the abstract capability of computing its area. This is an example of the simplest yet most fundamental OO design pattern called the Union Pattern.

The Union Pattern is the result of partitioning the sets of objects in the problem domain into disjoint subsets and consists of

A client of the Union Pattern uses instances of the concrete subclasses (Variant1, Variant2), but should only see them as AClass objects. The client class code should only concern itself with the public methods of AClass and should not need to check for the class type of the concrete instances it is working with. Conditional statements to distinguish the various cases are gone resulting in reduced code complexity, making the code easier to maintain.

NOTE: the term Union Pattern is not part of the standard pattern language in the design pattern community. Such a pattern is taken for granted in all OO design. Here we give it a name to facilitate the discussion of its use in all future designs.

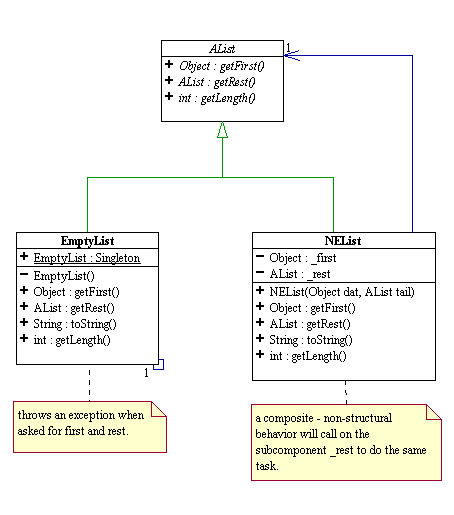

The following is another design for the functional Scheme-like list data structure that also makes use of the composite design pattern.

Each time we want to compute something new, we have to edit each class and add appropriate methods to each class. For example, if we want to find the last element in the list, we have to do three things:

This process of extending the capability of the list structure is error-prone at best and cannot be carried out if one does not own the source code for this structure. The system so designed is inherently cumbersome, rigid, and limited.

These design flaws come of the

lack of delineation between the intrinsic and primitive behavior of the

structure itself and the more complex behavior needed for a specific

application. The failure to decouple primitive and non-primitive operations also

causes reusability and extensibility problems. The weakness in bundling a data

structure with a predefined set of operations is that it presents a static

non-extensible interface to the client that cannot handle unforeseen future

requirements. Reusability and extensibility are more than just aesthetic

issues; in the real world, they are driven by powerful practical and economic

considerations. Computer science

students should be conditioned to design code with the knowledge that it will be

modified many times. In particular

is the need for the ability to add features after

the software has been delivered. Therefore one must seek to decouple the

data structures from the algorithms (or operations) that manipulate it. An

object-oriented approach to address this issue proceeds as follows.

Identify and separate the variant and the invariant behaviors.

Encapsulate the invariant behaviors into a system of classes.

Add "hooks" to this class to define communication protocols with other classes.

Encapsulate

the variant behaviors into a union of classes that comply with the above

protocols.

The result is a flexible system of co-operating objects that is not only reusable and extensible, but also easy to understand and maintain.

Let us illustrate the above process by applying it to the design of the immutable list structure and its algorithms.

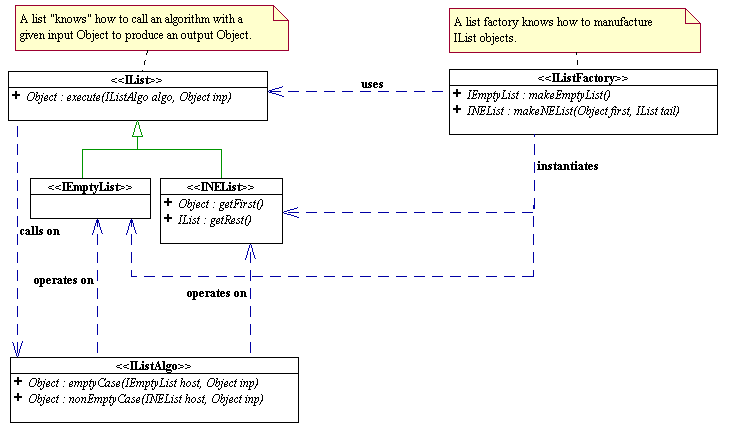

Here, the invariant is the intrinsic and primitive behavior of the list structure, IList, and the variants are the multitude of extrinsic and non-primitive algorithms that manipulate it, IListAlgo.

The recursive list structure is implemented using the composite design pattern and encapsulated with a minimal and complete set of primitive structural operations: getFirst() and getRest().

The hook method Object execute(IListAlgo ago, Object inp) defines the protocols for operating on the list structure. The hook works as if a IList announces to the outside world the following protocol:

“If you want me to execute your algorithm, encapsulate it into an object of type IListAlgo, hand it to me together with its inp object as parameters for my execute(). I will send your algorithm object the appropriate message for it to perform its task, and return you the result.

emptyCase(...) should be the part of the algorithm that deals with the case where I am empty.

nonEmptyCase(...) should be the part of the algorithm that deals with the case where I am not empty.”

IListAlgo and all of its concrete implementations forms a union of algorithms classes that can be sent to the list structure for execution.

The above design is an example of what is called the Visitor Pattern. Class IList is called the host and its method execute() is called a "hook" to the IListAlgo visitors. Via polymorphism, IList knows exactly what method to call on the specific IListAlgo visitor. This design turns the list structure into a (miniature) framework where control is inverted: one hands an algorithm to the structure to be executed instead of handing a structure to an algorithm to perform a computation. Since an IListAlgo only interacts with the list on which it operates via the list’s public interface, the list structure is capable of carrying out any conforming algorithm, past, present, or future. This is how reusability and extensibility is achieved.

Here is the design of the list framework again.

The following is a direct quote from the Design Patterns book by

Gamma, Helm, Johnson, and Vlissides (the Gang of Four - GoF).

"Frameworks thus emphasizes design reuse over code resuse...Reuse on this level leads to an inversion of control between the application and the

software on which it's based. When you use a toolkit (or a conventional subroutine library software for that matter), you write the main body of the

application and call the code you want to reuse. When you use a framework, you reuse the main body and write the code it calls...."

The linear recursive structure (IList) coupled with the visitors as shown in the

above is one of the simplest, non-trivial, and practical examples of frameworks.

It has the characteristic of "inversion of control" described in the quote. It illustrates the so-called

Holywood Programming Principle: don't call me, I will call you. Imagine the

IList union sitting in a library. When we write an algorithm on an IList in

conformance with its visitor interface, we are writing code for the IList to call and not the other way around. By adhering to the

IList framework's protocol, all algorithms on the IList can be developed much more quickly. And because they all have similar structures, they are much

easier to "maintain". The IList framework puts polymorphism to use in a very effective (and elegant!) way to reduce flow control and code

complexity.

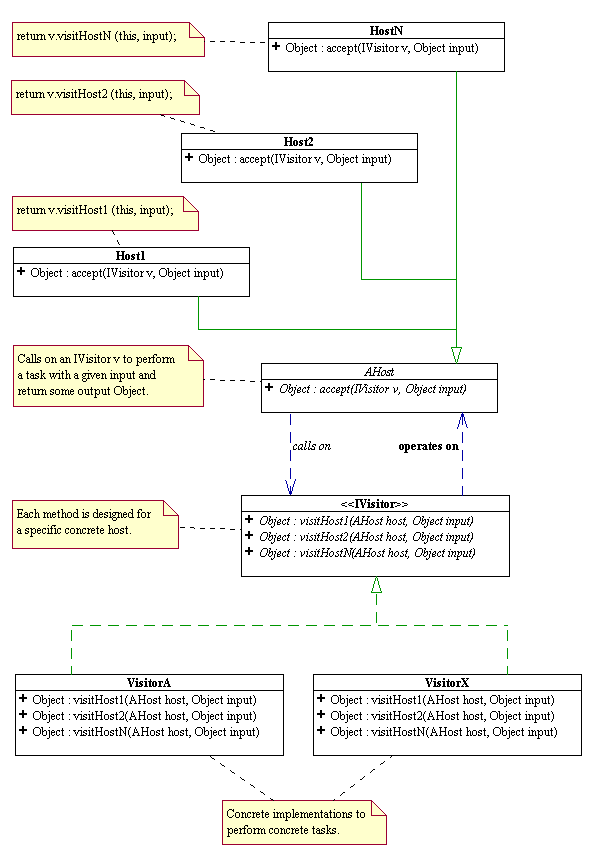

The visitor pattern is a framework for communication and collaboration between two union patterns: a "host" union and a "visitor" union. An abstract visitor is usually defined as an interface in Java. It has a separate method for each of the concrete variant of the host union. The abstract host has a method (called the "hook") to "accept" a visitor and leaves it up to each of its concrete variants to call the appropriate visitor method. This "decoupling" of the host's structural behaviors from the extrinsic algorithms on the host permits the addition of infinitely many external algorithms without changing any of the host union code. This extensibility only works if the taxonomy of the host union is stable and does not change. If we have to modify the host union, then we will have to modify ALL visitors as well!

NOTE: All the "state-less" visitors should be singletons.

dxnguyen@cs.rice.edu, Last Revised Sept. 20, 2002 Copyright 2002, Dung X. Nguyen - All rights reserved.